"Wisdom is not a product of schooling but of the lifelong attempt to acquire it."

~ Albert Einstein

Hail, friends with aging brains, we have good news: As we get older, our skin is not the only thing that wrinkles — our brains get wrinklier, too.

It's true that by age 50, the tips of our tongues are crowded with words that refuse to leap into consciousness, and it's true that certain types of information kick up a fuss when we try to learn them. But such things are mere annoyances when compared with scientific verification that wisdom really does come with age.

In a December 29, 2009 New York Times article titled "How to Train the Aging Brain," Times Health Editor Barbara Strauch made me feel younger immediately when she wrote that, due to increasing lifespans, middle age "now stretches from the 40s to late 60s." I liked this even better: "The brain, as it traverses middle age, gets better at recognizing the central idea, the big picture. If kept in good shape, the brain can continue to build pathways that help its owner recognize patterns and, as a consequence, see significance and even solutions much faster than a young person can."

Strauch, whose new book, The Secret Life of the Grown-up Brain, will be published on April 15, was back again in early February with "Brain Functions that Improve with Age" for a Harvard Business Review blog. She noted, "In areas as diverse as vocabulary and inductive reasoning, our brains function better than they did in our 20s."

A March 1, 2010 NPR story, "The Aging Brain Is Less Quick, But More Shrewd," is the latest addition to the stack of good news about old brains. UCLA brain researcher Gary Smalls says that in middle age, our "neuro-circuits fire more rapidly, as if you're going from dial-up to DSL" — in other words, our complex reasoning skills improve significantly as we age. Even better, constant learning and physical exercise make the whole wrinkly machine work better.

I don't know about you, but I feel smarter already.

"A man only becomes wise when he begins to calculate the approximate depth of his ignorance."

~ Gian Carlo Menotti

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Monday, March 29, 2010

Here's to Living in the Along

Over on Aloud, the blog I edit for New York Women in Communications, we've been profiling women past and present for Women's History Month. This is the profile I wrote about one of my favorite poets, Gwendolyn Brooks.

It is safe to say that poetry was Gwendolyn Brooks' true native language. Her first poem, "Eventide," was published in American Childhood magazine when she was just 13. She published her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, at age 28.

Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917, she spent almost all of her life in Chicago, and that city's people, especially its African American citizens, shaped and infused her work. The excellent biography on the Poetry Foundation Web site quotes an interview she did with Contemporary Literature magazine. She said, "I want to write poems that are non-compromising. I don't want to stop a concern with words doing good jobs, which has always been a concern of mine, but I want to write poems that will be meaningful."

And she did. She chronicled poverty and discrimination and she wrote movingly of those who had settled for dead-end lives. Her most famous poem, "We Real Cool," with its be-bop beat, talks about the hopelessness of the choices some men make.

In the late 1960s, when she wrote frequently about the sometimes violent struggle for racial equality in poems like "Riot," some criticized her as too "angry." But critic Janet Overmeyer had it right when, in an article about Gwendolyn Brooks in the Christian Science Monitor, she said her "particular, outstanding genius is her unsentimental regard and respect for all human beings...from her poet's craft bursts a whole gallery of wholly alive persons, preening, squabbling, loving, weeping."

That humanity is what I love most about the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks. You can feel her strength of spirit shine through in poems like this one.

Speech to the young: Speech to the Progress-Toward

Speech to the young: Speech to the Progress-Toward

Gwendolyn Brooks, who always lived in the along, was extremely prolific, writing hundreds of poems, numerous collections of poetry, an autobiography, a novel and several books of prose. It is a testament to her talent that she is one of the few modern poets to be celebrated in her lifetime. By age 30 she had won a Guggenheim fellowship, been named one of "10 young women to watch" by Mademoiselle and become a fellow in the American Academy of Arts & Letters. She became the first African American to win the Pulitzer prize in 1950, was named Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968 and became Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985. In 1994 she was selected by the National Endowment for the Humanities as a Jefferson Lecturer, the federal government's highest humanities award. The honors and awards continued until her death in 2000.

* * *

It is safe to say that poetry was Gwendolyn Brooks' true native language. Her first poem, "Eventide," was published in American Childhood magazine when she was just 13. She published her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, at age 28.

Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917, she spent almost all of her life in Chicago, and that city's people, especially its African American citizens, shaped and infused her work. The excellent biography on the Poetry Foundation Web site quotes an interview she did with Contemporary Literature magazine. She said, "I want to write poems that are non-compromising. I don't want to stop a concern with words doing good jobs, which has always been a concern of mine, but I want to write poems that will be meaningful."

And she did. She chronicled poverty and discrimination and she wrote movingly of those who had settled for dead-end lives. Her most famous poem, "We Real Cool," with its be-bop beat, talks about the hopelessness of the choices some men make.

We Real Cool

The pool players.

Seven at the golden shovel.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk Late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

In the late 1960s, when she wrote frequently about the sometimes violent struggle for racial equality in poems like "Riot," some criticized her as too "angry." But critic Janet Overmeyer had it right when, in an article about Gwendolyn Brooks in the Christian Science Monitor, she said her "particular, outstanding genius is her unsentimental regard and respect for all human beings...from her poet's craft bursts a whole gallery of wholly alive persons, preening, squabbling, loving, weeping."

That humanity is what I love most about the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks. You can feel her strength of spirit shine through in poems like this one.

Speech to the young: Speech to the Progress-Toward

Speech to the young: Speech to the Progress-TowardSay to them,

say to the down-keepers,

the sun-slappers,

the self-soilers,

the harmony-hushers,

"even if you are not ready for day

it cannot always be night."

You will be right.

For that is the hard home-run.

Live not for battles won.

Live not for the-end-of-the-song.

Live in the along.

Gwendolyn Brooks, who always lived in the along, was extremely prolific, writing hundreds of poems, numerous collections of poetry, an autobiography, a novel and several books of prose. It is a testament to her talent that she is one of the few modern poets to be celebrated in her lifetime. By age 30 she had won a Guggenheim fellowship, been named one of "10 young women to watch" by Mademoiselle and become a fellow in the American Academy of Arts & Letters. She became the first African American to win the Pulitzer prize in 1950, was named Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968 and became Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985. In 1994 she was selected by the National Endowment for the Humanities as a Jefferson Lecturer, the federal government's highest humanities award. The honors and awards continued until her death in 2000.

- Click here to listen to Gwendolyn Brooks talk about "We Real Cool" and then read it in her distinctive voice.

- Click here to learn more about Gwendolyn Brooks, read about her life and sample a selection of her poems on the Poetry Foundation's Web site.

Friday, March 26, 2010

How to Write About Science

"Don't worry when you are not recognized, but strive to be worthy of recognition."

~ Abraham Lincoln

Divinipotent Daily is fascinated by science and finds it thrilling (I know, cheap thrills) that the Internet offers an ever-expanding buffet of science blogs. At this point, there is so much to read, it's difficult to decide what to read next. That's why I was excited to learn that the organization Research Blogging has selected a few of the best science blogs as winners of its 2010 awards.

Let's focus on the winners in two categories: Best Lay-Level Blog (which refers not to horizontal blogging but to writing for lay people — meaning non-scientists like me and probably you) and Best Blog of the Year. And the winners are...one and the same person: British Science Writer Ed Yong, who more or less in his spare time writes a blog called Not Exactly Rocket Science. So let's see what Mr. Yong has been writing about.

The winning post in the Best Lay-Level Blog category has an unusual title, "Ballistic penises and corkscrew vaginas — the sexual battles of ducks." And that title describes, with complete accuracy, the subject of the blog. You know you're curious, but be forewarned: the post includes videos that would be rated XXX by a duck censor.

In announcing the selection of Not Exactly Rocket Science as Best Blog of the year, Research Blogging cited a variety of posts. At the top of the list was "Pocket Science — a psychopath's reward, and the mystery of the shark-bitten fossil poo." Note: psychopaths have nothing in common with fossilized poo. Instead, the post has two subjects: (1) a new theory about why psychopaths are so impulsive and (2) musings about why an ancient shark left bite marks in fossilized dung. I certainly won't spoil the surprise; you'll have to go read it.

In announcing the selection of Not Exactly Rocket Science as Best Blog of the year, Research Blogging cited a variety of posts. At the top of the list was "Pocket Science — a psychopath's reward, and the mystery of the shark-bitten fossil poo." Note: psychopaths have nothing in common with fossilized poo. Instead, the post has two subjects: (1) a new theory about why psychopaths are so impulsive and (2) musings about why an ancient shark left bite marks in fossilized dung. I certainly won't spoil the surprise; you'll have to go read it.

Congratulations, Mr. Yong. I look forward to learning more from your blog.

“I'll take any trophy. I don't care what it says on it.”

~ Mary-Louise Parker

~ Abraham Lincoln

Divinipotent Daily is fascinated by science and finds it thrilling (I know, cheap thrills) that the Internet offers an ever-expanding buffet of science blogs. At this point, there is so much to read, it's difficult to decide what to read next. That's why I was excited to learn that the organization Research Blogging has selected a few of the best science blogs as winners of its 2010 awards.

Let's focus on the winners in two categories: Best Lay-Level Blog (which refers not to horizontal blogging but to writing for lay people — meaning non-scientists like me and probably you) and Best Blog of the Year. And the winners are...one and the same person: British Science Writer Ed Yong, who more or less in his spare time writes a blog called Not Exactly Rocket Science. So let's see what Mr. Yong has been writing about.

The winning post in the Best Lay-Level Blog category has an unusual title, "Ballistic penises and corkscrew vaginas — the sexual battles of ducks." And that title describes, with complete accuracy, the subject of the blog. You know you're curious, but be forewarned: the post includes videos that would be rated XXX by a duck censor.

In announcing the selection of Not Exactly Rocket Science as Best Blog of the year, Research Blogging cited a variety of posts. At the top of the list was "Pocket Science — a psychopath's reward, and the mystery of the shark-bitten fossil poo." Note: psychopaths have nothing in common with fossilized poo. Instead, the post has two subjects: (1) a new theory about why psychopaths are so impulsive and (2) musings about why an ancient shark left bite marks in fossilized dung. I certainly won't spoil the surprise; you'll have to go read it.

In announcing the selection of Not Exactly Rocket Science as Best Blog of the year, Research Blogging cited a variety of posts. At the top of the list was "Pocket Science — a psychopath's reward, and the mystery of the shark-bitten fossil poo." Note: psychopaths have nothing in common with fossilized poo. Instead, the post has two subjects: (1) a new theory about why psychopaths are so impulsive and (2) musings about why an ancient shark left bite marks in fossilized dung. I certainly won't spoil the surprise; you'll have to go read it.Congratulations, Mr. Yong. I look forward to learning more from your blog.

“I'll take any trophy. I don't care what it says on it.”

~ Mary-Louise Parker

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Featured Creatures of the Month

“The man who regards his own life and that of his fellow creatures as meaningless is not merely unfortunate but almost disqualified for life.”

~ Albert Einstein

A couple of days ago Scientific American reported a discovery that adds a strange new meaning to the term "water wings": scientists have found the first known amphibious insect species. The critters in question are a type of Hawaiian moth caterpillars. And the big surprise is, their larvae do equally well in water and on land.

But that's not the strangest critter news of the month. Science writer and paleontology fancier Brian Switek reports on his blog Laelaps the discovery of two truly weird additions to the already weird menagerie of the Cambrian era, which lasted from 0.3 million to 1.7 million years ago (or, if you're a creationist, 10,000 years ago). It was a time when a vast profusion of new creatures burst into existence and the ancestors of most modern creatures first emerged.

The first critter, whose name is Herpetogaster collinsi, seems to be a shrimp on a stick with parsley growing from its head — a sort of self-generating shrimp salad. Switek writes, "Herpetogaster collinsi [is] the latest fossil to be named from the famous 505 million year old Burgess Shale of Canada." The Burgess Shale is one of our planet's richest sources of fossils — the Smithsonian Museum alone has over 65,000 specimens collected there.

The second new discovery, Kiisortoqia soperi (above), looks a bit more familiar, like a trilobite with feathers. Switek notes: "Found in the Early Cambrian (~540-510 million years ago) rocks of North Greenland, Kiisortoqia soperi was an arthropod with a simple head shield, a segmented body, and two long appendages sticking out in front of it." Pretty, isn't it. It's fascinating stuff; I recommend spending some time on Switek's blog to learn more.

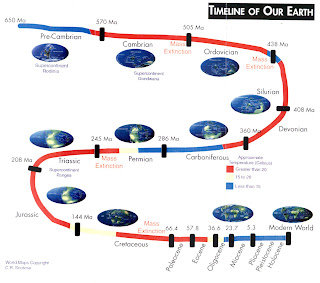

As the chart below illustrates, an awful lot has happened since the Cambrian era, and we humans missed most of it. Perhaps that's why so many of us love learning what the fossil record reveals.

"The earth is not a mere fragment of dead history, stratum upon stratum like the leaves of a book, to be studied by geologists and antiquaries chiefly, but living poetry like the leaves of a tree, which precede flowers and fruit / not a fossil earth, but a living earth; compared with whose great central life all animal and vegetable life is merely parasitic. Its throes will heave our exuviate from their graves."

~ Henry David Thoreau

~ Albert Einstein

A couple of days ago Scientific American reported a discovery that adds a strange new meaning to the term "water wings": scientists have found the first known amphibious insect species. The critters in question are a type of Hawaiian moth caterpillars. And the big surprise is, their larvae do equally well in water and on land.

But that's not the strangest critter news of the month. Science writer and paleontology fancier Brian Switek reports on his blog Laelaps the discovery of two truly weird additions to the already weird menagerie of the Cambrian era, which lasted from 0.3 million to 1.7 million years ago (or, if you're a creationist, 10,000 years ago). It was a time when a vast profusion of new creatures burst into existence and the ancestors of most modern creatures first emerged.

The first critter, whose name is Herpetogaster collinsi, seems to be a shrimp on a stick with parsley growing from its head — a sort of self-generating shrimp salad. Switek writes, "Herpetogaster collinsi [is] the latest fossil to be named from the famous 505 million year old Burgess Shale of Canada." The Burgess Shale is one of our planet's richest sources of fossils — the Smithsonian Museum alone has over 65,000 specimens collected there.

The second new discovery, Kiisortoqia soperi (above), looks a bit more familiar, like a trilobite with feathers. Switek notes: "Found in the Early Cambrian (~540-510 million years ago) rocks of North Greenland, Kiisortoqia soperi was an arthropod with a simple head shield, a segmented body, and two long appendages sticking out in front of it." Pretty, isn't it. It's fascinating stuff; I recommend spending some time on Switek's blog to learn more.

As the chart below illustrates, an awful lot has happened since the Cambrian era, and we humans missed most of it. Perhaps that's why so many of us love learning what the fossil record reveals.

"The earth is not a mere fragment of dead history, stratum upon stratum like the leaves of a book, to be studied by geologists and antiquaries chiefly, but living poetry like the leaves of a tree, which precede flowers and fruit / not a fossil earth, but a living earth; compared with whose great central life all animal and vegetable life is merely parasitic. Its throes will heave our exuviate from their graves."

~ Henry David Thoreau

Monday, March 22, 2010

Every Picture Tells a Story

“When words become unclear, I shall focus with photographs. When images become inadequate, I shall be content with silence.”

~ Ansel Adams

The Internet is rich in photography. It is everywhere — in the online collections of museums and libraries and also in the handcrafted collections of photo enthusiasts.

One of my favorite places to spend time is the Shorpy Historic Photo Archive. Subscribe and every morning you will find something wonderful in your e-mail. Yesterday it was this comical scene of a group of dour old girls struggling to enjoy themselves on a beach in Sarasota, Florida, in 1941.

On another day, the photo might be a turn-of-the century street scene, the interior of an old shop or perhaps a close-up of an interesting face from long ago.

Another, very different photo collection is the one being assembled by Jonathan Harris. About a week ago I wrote about the We Feel Fine project, Harris's exploration of emotions on the Internet. But he has another project (actually several, but let's focus on one). When he turned 30 last summer, he decided to take one photo every day and post it to his Web site. Some days he posts just a photo and perhaps a brief caption. But on days like this one he writes a story about where he's been and whom he's met, and you end up wishing you had been with him.

Or, for a completely different experience, try New York Daily Photo. It's exactly what it sounds like: daily photos of life in New York City.

Other great places to explore: the photo archives of the Smithsonian Museum and the Library of Congress; the New York Public Library's digital photo collection at the Commons on Flickr; and Life magazine's photo archive on Google Images.

“All photographs are there to remind us of what we forget. In this — as in other ways — they are the opposite of paintings. Paintings record what the painter remembers. Because each one of us forgets different things, a photo more than a painting may change its meaning according to who is looking at it.”

~ John Berger

~ Ansel Adams

The Internet is rich in photography. It is everywhere — in the online collections of museums and libraries and also in the handcrafted collections of photo enthusiasts.

One of my favorite places to spend time is the Shorpy Historic Photo Archive. Subscribe and every morning you will find something wonderful in your e-mail. Yesterday it was this comical scene of a group of dour old girls struggling to enjoy themselves on a beach in Sarasota, Florida, in 1941.

On another day, the photo might be a turn-of-the century street scene, the interior of an old shop or perhaps a close-up of an interesting face from long ago.

Another, very different photo collection is the one being assembled by Jonathan Harris. About a week ago I wrote about the We Feel Fine project, Harris's exploration of emotions on the Internet. But he has another project (actually several, but let's focus on one). When he turned 30 last summer, he decided to take one photo every day and post it to his Web site. Some days he posts just a photo and perhaps a brief caption. But on days like this one he writes a story about where he's been and whom he's met, and you end up wishing you had been with him.

Or, for a completely different experience, try New York Daily Photo. It's exactly what it sounds like: daily photos of life in New York City.

Other great places to explore: the photo archives of the Smithsonian Museum and the Library of Congress; the New York Public Library's digital photo collection at the Commons on Flickr; and Life magazine's photo archive on Google Images.

“All photographs are there to remind us of what we forget. In this — as in other ways — they are the opposite of paintings. Paintings record what the painter remembers. Because each one of us forgets different things, a photo more than a painting may change its meaning according to who is looking at it.”

~ John Berger

Friday, March 19, 2010

No More Multitasking

“The sound shivers through the walls, through the table, through the window frame, and into my finger. These distraction-oholics. These focus-ophobics. Old George Orwell got it backward. Big Brother isn't watching. He's singing and dancing. He's pulling rabbits out of a hat. Big Brother's holding your attention every moment you're awake. He's making sure you're always distracted. He's making sure you're fully absorbed... and this being fed, it's worse than being watched. With the world always filling you, no one has to worry about what's in your mind. With everyone's imagination atrophied, no one will ever be a threat to the world.”

~ Chuck Palahniuk

I'm done with pretending. Multitasking is not an efficiency booster, it's just a four-syllable word for being distracted.

Yesterday, while chatting with my husband about something on the local TV news and simultaneously scanning the morning's e-mail, I misread a note from a client and responded with a stupid question. A few minutes later, while making dinner plans with two friends, I failed to notice that my calendar had jumped to 2011.

As author and molecular biologist John Medina wrote in his 2008 book Brain Rules, "research shows that we can’t multitask. We are biologically incapable of processing attention-rich inputs simultaneously." What we are actually doing is switching back and forth from one task to another, and each time we switch we inhibit our efficiency.

But it gets worse. Multitasking also makes us poor learners. In Science Daily (June 26, 2006), Russell Poldtrack, an associate professor of psychology at UCLA, described a multitasking study he and his team had done. They found that even if you learn while multitasking, "that learning is less flexible and more specialized, so you cannot retrieve the information as easily." The study's conclusion: "The best thing you can do to improve your memory is to pay attention to the things you want to remember." I think my parents told me that about 50 years ago.

While I've never been one to multitask while driving — in bad road conditions, I don't even like to talk to the person in the car with me — I've become a manic multitasker at work. It's not unusual for me to have a writing project open on the monitor connected to my G4 and social media running on my Macbook.

But I'm starting to rein things in, step by step. Step one: I'm doing my research old school (assuming the school dates from the digital era); I'm downloading online research, taking notes and then working from the notes instead of referring back to online sources, which frequently lead to charming but time-consuming diversions. Step two: I'm writing on my creaky old G4; because it's too slow for most of what happens online, it discourages digressions into e-mail, Twitter, Facebook and other destinations on the million-ring-circus known as the Internet. Step three: when all else fails, I grab my notes and head for a quiet corner of the local coffee shop.

If anyone has tips on kicking the multitasking habit, I'd love to hear them.

For more on why multitasking is a bad idea, see the rather frightening August 2009 Wired Science story, "Multitasking Muddles Brains, Even When the Computer Is Off."

“Hutchison's Law: Any occurrence requiring undivided attention will be accompanied by a compelling distraction.”

~ Robert Bloch

~ Chuck Palahniuk

I'm done with pretending. Multitasking is not an efficiency booster, it's just a four-syllable word for being distracted.

Yesterday, while chatting with my husband about something on the local TV news and simultaneously scanning the morning's e-mail, I misread a note from a client and responded with a stupid question. A few minutes later, while making dinner plans with two friends, I failed to notice that my calendar had jumped to 2011.

As author and molecular biologist John Medina wrote in his 2008 book Brain Rules, "research shows that we can’t multitask. We are biologically incapable of processing attention-rich inputs simultaneously." What we are actually doing is switching back and forth from one task to another, and each time we switch we inhibit our efficiency.

But it gets worse. Multitasking also makes us poor learners. In Science Daily (June 26, 2006), Russell Poldtrack, an associate professor of psychology at UCLA, described a multitasking study he and his team had done. They found that even if you learn while multitasking, "that learning is less flexible and more specialized, so you cannot retrieve the information as easily." The study's conclusion: "The best thing you can do to improve your memory is to pay attention to the things you want to remember." I think my parents told me that about 50 years ago.

While I've never been one to multitask while driving — in bad road conditions, I don't even like to talk to the person in the car with me — I've become a manic multitasker at work. It's not unusual for me to have a writing project open on the monitor connected to my G4 and social media running on my Macbook.

But I'm starting to rein things in, step by step. Step one: I'm doing my research old school (assuming the school dates from the digital era); I'm downloading online research, taking notes and then working from the notes instead of referring back to online sources, which frequently lead to charming but time-consuming diversions. Step two: I'm writing on my creaky old G4; because it's too slow for most of what happens online, it discourages digressions into e-mail, Twitter, Facebook and other destinations on the million-ring-circus known as the Internet. Step three: when all else fails, I grab my notes and head for a quiet corner of the local coffee shop.

If anyone has tips on kicking the multitasking habit, I'd love to hear them.

For more on why multitasking is a bad idea, see the rather frightening August 2009 Wired Science story, "Multitasking Muddles Brains, Even When the Computer Is Off."

“Hutchison's Law: Any occurrence requiring undivided attention will be accompanied by a compelling distraction.”

~ Robert Bloch

Monday, March 15, 2010

The Sublime and the Silly of It

"Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler."

~ Albert Einstein

For many years a very special greeting card hung by my desk. It was Einstein on a bicycle, as in this photograph, but on the card he was not alone. On his head stood a dog. The dog was balancing a pole on which a cat and a mouse perched. All three animals — dog, cat and mouse — were standing on one leg, each performing a trick.

The card was, for me, a visual metaphor for all that makes science fun for non-scientists. Einstein: always fascinating. Einstein on a bicycle: better because that makes him more like us. Dog, cat and mouse on a bicycle with Einstein, all fighting the force of gravity and no doubt demonstrating various principles of physics: hilarious.

I think Einstein would have loved it. After all, this shot by UPI photographer Albert Sasse — taken on Einstein's 72nd birthday in 1951 — was one of his favorite photos; he is said to have ordered nine copies of it.

Yesterday would have been Albert Einstein’s 131st birthday. Wherever in the universe your molecules are, happy belated birthday, Mr. E!

"Gravitation is not responsible for people falling in love."

~ Albert Einstein

~ Albert Einstein

For many years a very special greeting card hung by my desk. It was Einstein on a bicycle, as in this photograph, but on the card he was not alone. On his head stood a dog. The dog was balancing a pole on which a cat and a mouse perched. All three animals — dog, cat and mouse — were standing on one leg, each performing a trick.

The card was, for me, a visual metaphor for all that makes science fun for non-scientists. Einstein: always fascinating. Einstein on a bicycle: better because that makes him more like us. Dog, cat and mouse on a bicycle with Einstein, all fighting the force of gravity and no doubt demonstrating various principles of physics: hilarious.

I think Einstein would have loved it. After all, this shot by UPI photographer Albert Sasse — taken on Einstein's 72nd birthday in 1951 — was one of his favorite photos; he is said to have ordered nine copies of it.

Yesterday would have been Albert Einstein’s 131st birthday. Wherever in the universe your molecules are, happy belated birthday, Mr. E!

"Gravitation is not responsible for people falling in love."

~ Albert Einstein

Friday, March 12, 2010

It's Friday and We're Feeling Better

"I feel the tears begin to form again as I try and push away the feeling of her looking down on me again."

"I simply want to feel good about the work I do and earn a salary which allows me to live."

"I feel like I'm good enough, but does she."

"I feel more sure of myself just by writing down what I want to do in my life."

"I feel as if someone has taken my bra."

The statements above were collected in the hours just before I began writing today's post by We Feel Fine, a Web site that describes itself as "an exploration of human emotion on a global scale." We Feel Fine is powered by a program that scours the world's blogs every few minutes for statements starting "I feel..." or "I am feeling..."

We Feel Fine was created in 2005 by Jonathan Harris, an extravagantly gifted young artist with a degree in computer science from Princeton, and Sep Kamvar, another artist whose day job is professor of computational mathematics at Stanford University. I first became aware of the project in 2007, when Harris's TED talk about "the Web's secret stories" was posted online. His second talk, "Jonathan Harris collects stories," is even more fascinating.

In December 2009, Harris and Kamvar packaged some of their more fascinating findings about feelings into a beautifully designed book, "We Feel Fine: An Almanac of Human Emotion." One thing you will discover: when we humans write about our feelings, we are surprisingly poetic.

By the way, the most common feeling in the past 24 hours is "better." Things are looking up!

“Tell me what you feel in your room when the full moon is shining in upon you and your lamp is dying out, and I will tell you how old you are, and I shall know if you are happy."

~ Henri Frederic Amiel

"I simply want to feel good about the work I do and earn a salary which allows me to live."

"I feel like I'm good enough, but does she."

"I feel more sure of myself just by writing down what I want to do in my life."

"I feel as if someone has taken my bra."

The statements above were collected in the hours just before I began writing today's post by We Feel Fine, a Web site that describes itself as "an exploration of human emotion on a global scale." We Feel Fine is powered by a program that scours the world's blogs every few minutes for statements starting "I feel..." or "I am feeling..."

We Feel Fine was created in 2005 by Jonathan Harris, an extravagantly gifted young artist with a degree in computer science from Princeton, and Sep Kamvar, another artist whose day job is professor of computational mathematics at Stanford University. I first became aware of the project in 2007, when Harris's TED talk about "the Web's secret stories" was posted online. His second talk, "Jonathan Harris collects stories," is even more fascinating.

In December 2009, Harris and Kamvar packaged some of their more fascinating findings about feelings into a beautifully designed book, "We Feel Fine: An Almanac of Human Emotion." One thing you will discover: when we humans write about our feelings, we are surprisingly poetic.

By the way, the most common feeling in the past 24 hours is "better." Things are looking up!

“Tell me what you feel in your room when the full moon is shining in upon you and your lamp is dying out, and I will tell you how old you are, and I shall know if you are happy."

~ Henri Frederic Amiel

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Sometimes Evolutionary Changes Seem Inevitable

“What but the wolf's tooth whittled so fine

The fleet limbs of the antelope?

What but fear winged the birds, and hunger

Jewelled with such eyes the great goshawk's head?”

~ Robinson Jeffers

Paleontologist Darren Naish has been a little bit obsessed by babirusas, a mammal that is not extinct but perhaps should be. The babirusa is a pig-like mammal that can be found in Sulawesi and parts of Indonesia. Its principal features are the two pairs of huge tusks that grow backward out of its mouth and over its head.

Pretty, isn't he?

On his blog, Tetrapod Zoology (Tet Zoo for short), Naish has written often about babirusas and particularly about his quest for an example of a babirusa whose tusk had grown so far back it had pierced its skull. This week he is extremely excited to announce that he has found one.

I don't want to spoil the surprise, so head on over to Tetrapod Zoology and take a look.

“Most species do their own evolving, making it up as they go along, which is the way Nature intended.”

~ Terry Pratchett

The fleet limbs of the antelope?

What but fear winged the birds, and hunger

Jewelled with such eyes the great goshawk's head?”

~ Robinson Jeffers

Paleontologist Darren Naish has been a little bit obsessed by babirusas, a mammal that is not extinct but perhaps should be. The babirusa is a pig-like mammal that can be found in Sulawesi and parts of Indonesia. Its principal features are the two pairs of huge tusks that grow backward out of its mouth and over its head.

Pretty, isn't he?

On his blog, Tetrapod Zoology (Tet Zoo for short), Naish has written often about babirusas and particularly about his quest for an example of a babirusa whose tusk had grown so far back it had pierced its skull. This week he is extremely excited to announce that he has found one.

I don't want to spoil the surprise, so head on over to Tetrapod Zoology and take a look.

“Most species do their own evolving, making it up as they go along, which is the way Nature intended.”

~ Terry Pratchett

Monday, March 8, 2010

What You See v. What You Get

"The work of science is to substitute facts for appearances, and demonstrations for impressions."

~ John Ruskin

About five years ago I was serving jury duty and was assigned to a pool being considered for a street crime case. After the normal voir dire, I was one of 12 people still sitting in the jury box. At this point the judge came in to explain a peculiarity of the case: the only evidence against the defendant was the eyewitness testimony of the mugging victim, who had seen his knife-wielding victimizer only once, on the night of the crime two years earlier. She asked, "Does anyone have a problem with that?" I raised my hand.

Standing in front of the judge like a defense attorney on Law & Order, I explained that in New York's bad old days, I had been the victim of one attempted mugging, one attempted assault and one robbery at gunpoint. And based on my experience, I did not believe the victim in this case could accurately identify an ordinary-looking attacker he had seen only once, under stress, after a two-year delay.

Here is why. The first time someone tried to mug me, the attacker was a peculiar-looking man with skin the color of lightly toasted Wonder Bread and a tight corona of dirty blond curls; he would have been easy to identify, had anybody in the mugbooks looked remotely like him.

Tangent: Have you ever sat in a police station leafing through old-fashioned mugbooks? The first time I did it, a stooped, gnarly cop right out of central casting repeatedly came to me with photos of swarthy men, or perhaps multiple photos of the same swarthy man. "Is this the guy?" I almost felt bad the first few times I reminded him that my mugger looked nothing like that.

The second man who tried to attack me was ordinary looking — so much so, several pages worth of mugbook faces looked at least a little bit like him. I was good at portraiture, so two or three days after the incident I sat down and tried to sketch him. I very quickly realized that my memory was adding false details — eyes like someone I knew, hair like someone in the mugbook. The truth was, during the incident my attention had been not on the man's face and but on the knife he was carrying.

In the third attack there were two criminals, and one put a gun to my head. They were a total blur from the get-go; my focus had been on my possessions as they disappeared down the street into the darkness. The judge reminded me that jurors are instructed to base their conclusions only on the evidence presented in the case. I reminded her that human nature was likely to overrule my best intentions. I was released back into the jury pool.

Scientists tell us our eyes show us only what evolution has decreed worth seeing. We see a narrow swath of the visible spectrum and completely miss what's outside of it — the worlds of infrared and ultraviolet, for example — while other creatures, including many insects and birds, can see a much broader spectrum. Our brains concoct three-dimensional images from the two-dimensional input provided by our stereoscopic vision. We are prey to optical illusions of many kinds.

Researchers have developed some interesting experiments to test visual acuity. One of these involves a video of students playing basketball. If you were to participate in this experiment, you would be told to find the students in the white t-shirts and watch them carefully, counting how many times they pass the basketball by throwing it and simultaneously counting how many times they pass it by bouncing it. Take a look at the video now — it's less than a minute long — and try the experiment. Be sure to keep a careful count of the passes and whether they are throws or bounces. Just watch it once — no cheating. We'll come back to the video and see how well you did in a moment.

Yesterday I attended a lecture by Marvin Chun, a cognitive scientist and professor of psychology at Yale. He spoke about fMRI studies of the brain areas that respond to faces and places. Interestingly, imagined places and faces stimulate a response almost as strong as real ones. Also interesting: gearheads respond to cars as if they were seeing members of their families!

Yesterday I attended a lecture by Marvin Chun, a cognitive scientist and professor of psychology at Yale. He spoke about fMRI studies of the brain areas that respond to faces and places. Interestingly, imagined places and faces stimulate a response almost as strong as real ones. Also interesting: gearheads respond to cars as if they were seeing members of their families!

And speaking of fMRIs, another recent study found that our eyes and brains find the images they produce are so persuasive, we are likely to believe even dodgy interpretations. Even scientists suffer from this illusion. You can download a PDF of the study here. (And thank you to the neuroscientist known on Twitter as @mocost for alerting me to it.)

Tricks of the eye can be entertaining, too. Take a look at the elephant above; notice anything funny about it? You can see many more optical illusions on this Web site.

Although our eyes lie unintentionally, they can still wreak havoc on people's lives. Between 1992 (when the Innocence Project first brought DNA testing to bear on wrongful convictions) and January 2010, some 249 defendants were exonerated of serious crimes. Some had spent decades in prison. In three quarters of the cases, the original convictions were based entirely or in part on eyewitness testimony. As this 2009 60 Minutes episode points out, our eyes lie.

Now, about that video: Did you see this guy? Most people don't.

"Appearances to the mind are of four kinds. Things either are what they appear to be; or they neither are, nor appear to be; or they are, and do not appear to be; or they are not, and yet appear to be. Rightly to aim in all these cases is the wise man's task."~ Epictetus

~ John Ruskin

About five years ago I was serving jury duty and was assigned to a pool being considered for a street crime case. After the normal voir dire, I was one of 12 people still sitting in the jury box. At this point the judge came in to explain a peculiarity of the case: the only evidence against the defendant was the eyewitness testimony of the mugging victim, who had seen his knife-wielding victimizer only once, on the night of the crime two years earlier. She asked, "Does anyone have a problem with that?" I raised my hand.

Standing in front of the judge like a defense attorney on Law & Order, I explained that in New York's bad old days, I had been the victim of one attempted mugging, one attempted assault and one robbery at gunpoint. And based on my experience, I did not believe the victim in this case could accurately identify an ordinary-looking attacker he had seen only once, under stress, after a two-year delay.

Here is why. The first time someone tried to mug me, the attacker was a peculiar-looking man with skin the color of lightly toasted Wonder Bread and a tight corona of dirty blond curls; he would have been easy to identify, had anybody in the mugbooks looked remotely like him.

Tangent: Have you ever sat in a police station leafing through old-fashioned mugbooks? The first time I did it, a stooped, gnarly cop right out of central casting repeatedly came to me with photos of swarthy men, or perhaps multiple photos of the same swarthy man. "Is this the guy?" I almost felt bad the first few times I reminded him that my mugger looked nothing like that.

The second man who tried to attack me was ordinary looking — so much so, several pages worth of mugbook faces looked at least a little bit like him. I was good at portraiture, so two or three days after the incident I sat down and tried to sketch him. I very quickly realized that my memory was adding false details — eyes like someone I knew, hair like someone in the mugbook. The truth was, during the incident my attention had been not on the man's face and but on the knife he was carrying.

In the third attack there were two criminals, and one put a gun to my head. They were a total blur from the get-go; my focus had been on my possessions as they disappeared down the street into the darkness. The judge reminded me that jurors are instructed to base their conclusions only on the evidence presented in the case. I reminded her that human nature was likely to overrule my best intentions. I was released back into the jury pool.

Scientists tell us our eyes show us only what evolution has decreed worth seeing. We see a narrow swath of the visible spectrum and completely miss what's outside of it — the worlds of infrared and ultraviolet, for example — while other creatures, including many insects and birds, can see a much broader spectrum. Our brains concoct three-dimensional images from the two-dimensional input provided by our stereoscopic vision. We are prey to optical illusions of many kinds.

Researchers have developed some interesting experiments to test visual acuity. One of these involves a video of students playing basketball. If you were to participate in this experiment, you would be told to find the students in the white t-shirts and watch them carefully, counting how many times they pass the basketball by throwing it and simultaneously counting how many times they pass it by bouncing it. Take a look at the video now — it's less than a minute long — and try the experiment. Be sure to keep a careful count of the passes and whether they are throws or bounces. Just watch it once — no cheating. We'll come back to the video and see how well you did in a moment.

Yesterday I attended a lecture by Marvin Chun, a cognitive scientist and professor of psychology at Yale. He spoke about fMRI studies of the brain areas that respond to faces and places. Interestingly, imagined places and faces stimulate a response almost as strong as real ones. Also interesting: gearheads respond to cars as if they were seeing members of their families!

Yesterday I attended a lecture by Marvin Chun, a cognitive scientist and professor of psychology at Yale. He spoke about fMRI studies of the brain areas that respond to faces and places. Interestingly, imagined places and faces stimulate a response almost as strong as real ones. Also interesting: gearheads respond to cars as if they were seeing members of their families!And speaking of fMRIs, another recent study found that our eyes and brains find the images they produce are so persuasive, we are likely to believe even dodgy interpretations. Even scientists suffer from this illusion. You can download a PDF of the study here. (And thank you to the neuroscientist known on Twitter as @mocost for alerting me to it.)

Tricks of the eye can be entertaining, too. Take a look at the elephant above; notice anything funny about it? You can see many more optical illusions on this Web site.

Although our eyes lie unintentionally, they can still wreak havoc on people's lives. Between 1992 (when the Innocence Project first brought DNA testing to bear on wrongful convictions) and January 2010, some 249 defendants were exonerated of serious crimes. Some had spent decades in prison. In three quarters of the cases, the original convictions were based entirely or in part on eyewitness testimony. As this 2009 60 Minutes episode points out, our eyes lie.

Now, about that video: Did you see this guy? Most people don't.

"Appearances to the mind are of four kinds. Things either are what they appear to be; or they neither are, nor appear to be; or they are, and do not appear to be; or they are not, and yet appear to be. Rightly to aim in all these cases is the wise man's task."~ Epictetus

Friday, March 5, 2010

Solving Problems by Knowing Less

"Science is the belief in the ignorance of the experts."

~ Richard Feynman

One of the brainy science people I follow on Twitter recently posted a link to an interesting talk by neuroscientist Jonah Lehrer. The forum was last October's PopTech 2009, one of those gatherings where smart people from different fields (who do not run our world but probably should) meet to share their insights.

In a talk that ranged from Thorstein Veblen to Albert Einstein to General Motors, Lehrer focused on the value of being an outsider — of seeing a problem with fresh eyes. As he noted and more and more organizations are discovering, outsiders are often the only people who can solve stubborn conundrums.

Lehrer cites the example of InnoCentive.com, a Web site that functions as the go-to help center for large organizations when they run into particularly tough, solution-resistant problems.

As this screen shot indicates, companies — even NASA — post their problems on InnoCentive, along with a substantial cash reward and a deadline. And as it turns out, when problems are solved, the solution tends to come not from an expert in the specific field but from a scientist with related but different knowledge. It's a brief talk, only 10 minutes or so, and worth watching. See it here.

While I was listening to Lehrer's PopTech talk, I was reminded of an article he wrote in the January 2010 issue of Wired — "Accept Defeat: The Neuroscience of Screwing Up." The topic was how to tell a laboratory "error" from an unexpected breakthrough. The best approach: get a diverse group of people to review the problem. (If you're feeling deja vu all over again, note that Divinipotent Daily wrote about this in early January.)

Lehrer and InnoCentive are obviously not the first to discover the value of putting fresh eyes on a problem. It's something most of us know intuitively. I will always remember the shock of attending my first few meetings in a conference room at a large corporation. Having spent my career until then in unconventional entrepreneurial companies, I immediately realized that almost nothing was ever accomplished until the big dogs left the room. The meetings were colossal time-wasters, but the people in charge — the so-called experts — never questioned whether this was really the way to get things done.

If you'd like to learn more about solving problems by knowing less, Harvard has a working paper, "The Value of Openness in Scientific Problem Solving," available for download (free) here.

"Always listen to experts. They'll tell you what can't be done and why. Then do it."

~ Robert Heinlein

~ Richard Feynman

One of the brainy science people I follow on Twitter recently posted a link to an interesting talk by neuroscientist Jonah Lehrer. The forum was last October's PopTech 2009, one of those gatherings where smart people from different fields (who do not run our world but probably should) meet to share their insights.

In a talk that ranged from Thorstein Veblen to Albert Einstein to General Motors, Lehrer focused on the value of being an outsider — of seeing a problem with fresh eyes. As he noted and more and more organizations are discovering, outsiders are often the only people who can solve stubborn conundrums.

Lehrer cites the example of InnoCentive.com, a Web site that functions as the go-to help center for large organizations when they run into particularly tough, solution-resistant problems.

As this screen shot indicates, companies — even NASA — post their problems on InnoCentive, along with a substantial cash reward and a deadline. And as it turns out, when problems are solved, the solution tends to come not from an expert in the specific field but from a scientist with related but different knowledge. It's a brief talk, only 10 minutes or so, and worth watching. See it here.

While I was listening to Lehrer's PopTech talk, I was reminded of an article he wrote in the January 2010 issue of Wired — "Accept Defeat: The Neuroscience of Screwing Up." The topic was how to tell a laboratory "error" from an unexpected breakthrough. The best approach: get a diverse group of people to review the problem. (If you're feeling deja vu all over again, note that Divinipotent Daily wrote about this in early January.)

Lehrer and InnoCentive are obviously not the first to discover the value of putting fresh eyes on a problem. It's something most of us know intuitively. I will always remember the shock of attending my first few meetings in a conference room at a large corporation. Having spent my career until then in unconventional entrepreneurial companies, I immediately realized that almost nothing was ever accomplished until the big dogs left the room. The meetings were colossal time-wasters, but the people in charge — the so-called experts — never questioned whether this was really the way to get things done.

If you'd like to learn more about solving problems by knowing less, Harvard has a working paper, "The Value of Openness in Scientific Problem Solving," available for download (free) here.

"Always listen to experts. They'll tell you what can't be done and why. Then do it."

~ Robert Heinlein

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Remembering Margaret Mead

"Every time we liberate a woman, we liberate a man."

~ Margaret Mead

March is Women's History Month, and I've been thinking a lot about the women who influenced me most when I was young. At or near the top of my list is cultural anthropologist, outspoken activist and all-around free thinker Margaret Mead.

March is Women's History Month, and I've been thinking a lot about the women who influenced me most when I was young. At or near the top of my list is cultural anthropologist, outspoken activist and all-around free thinker Margaret Mead.

In 2001, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her birth, the Library of Congress mounted an expansive exhibit, pulling generously from its collection of 500,000 Margaret Mead items. Selected parts of that exhibit are online now, and it is truly fascinating stuff. See it here.

In 2001, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her birth, the Library of Congress mounted an expansive exhibit, pulling generously from its collection of 500,000 Margaret Mead items. Selected parts of that exhibit are online now, and it is truly fascinating stuff. See it here.

Here are a few of the smart and funny things she had to say:

"I must admit that I personally measure success in terms of the contributions an individual makes to her or his fellow human beings."

"Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else."

"One of the oldest human needs is having someone to wonder where you are when you don't come home at night."

"I have spent most of my life studying the lives of other peoples — faraway peoples — so that Americans might better understand themselves."

"A small group of thoughtful people could change the world. Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has."

~ Margaret Mead

March is Women's History Month, and I've been thinking a lot about the women who influenced me most when I was young. At or near the top of my list is cultural anthropologist, outspoken activist and all-around free thinker Margaret Mead.

March is Women's History Month, and I've been thinking a lot about the women who influenced me most when I was young. At or near the top of my list is cultural anthropologist, outspoken activist and all-around free thinker Margaret Mead.I'm not completely sure what brought Margaret Mead to my attention. It was probably one of one of her frequent television appearances — she was a semi-regular on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. I must have been ten or eleven at the time, and I remember being impressed by how confident and self-possessed she seemed. She also had a mischievous edge that radiated through her matronly exterior. She was a little woman with large and impressively exotic accomplishments who spoke about things that just didn't come up at my mother's bridge club meetings — not everyday attributes for a woman in the 1950s. The more I learned more about her, especially her advocacy on behalf of women's rights, civil rights and the rights of children, the more impressed I became.

If you're not familiar with Margaret Mead, here's a brief recap. She was born in 1901 to a Pennsylvania Quaker family that valued education; her father was a professor at the Wharton School and her mother was a sociologist. Margaret earned her master's degree in anthropology at Columbia in 1924, studying under Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, before heading off to Polynesia for field work. When she returned to the U.S. in 1926, Margaret took a job with the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where she continued working for the next 43 years. She earned her PhD from Columbia in 1929.

Her first book, Coming of Age in Samoa, is a study of the lives, values, customs and sex habits of young Samoans; published in 1928, it made her a star. She authored or co-authored some nineteen books in her lifetime. She also found time to marry three times; all were anthropologists and the last was the famous British scientist and anthropologist Gregory Bateson, with whom she had one daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson, who grew up to become a cultural anthropologist, too. Margaret was believed to be bisexual and, as far as I can tell, never backed down from a fight.

In Washington in 1969, during one of her many visits to testify before Congress, she stirred up one of her last controversies when she endorsed legalizing marijuana. It inspired cartoonist Mike Peters to draw the cartoon at right for the Dayton Daily News.

In Washington in 1969, during one of her many visits to testify before Congress, she stirred up one of her last controversies when she endorsed legalizing marijuana. It inspired cartoonist Mike Peters to draw the cartoon at right for the Dayton Daily News.

As the Institute for Intercultural Studies points out on its Web site, "When Margaret Mead died in 1978, she was the most famous anthropologist in the world. Indeed, it was through her work that many people learned about anthropology and its holistic vision of the human species."

In Washington in 1969, during one of her many visits to testify before Congress, she stirred up one of her last controversies when she endorsed legalizing marijuana. It inspired cartoonist Mike Peters to draw the cartoon at right for the Dayton Daily News.

In Washington in 1969, during one of her many visits to testify before Congress, she stirred up one of her last controversies when she endorsed legalizing marijuana. It inspired cartoonist Mike Peters to draw the cartoon at right for the Dayton Daily News.As the Institute for Intercultural Studies points out on its Web site, "When Margaret Mead died in 1978, she was the most famous anthropologist in the world. Indeed, it was through her work that many people learned about anthropology and its holistic vision of the human species."

In 2001, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her birth, the Library of Congress mounted an expansive exhibit, pulling generously from its collection of 500,000 Margaret Mead items. Selected parts of that exhibit are online now, and it is truly fascinating stuff. See it here.

In 2001, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her birth, the Library of Congress mounted an expansive exhibit, pulling generously from its collection of 500,000 Margaret Mead items. Selected parts of that exhibit are online now, and it is truly fascinating stuff. See it here. Margaret Mead also lives on in the online archives of the American Museum of Natural History, which has a trove of archival footage. But for a more accessible view, I recommend this brief video filmed by a close friend about a year before she died. I watched it before I sat down to write this, and it reminded me of the quiet confidence and humor that had made me admire her in the first place.

"I must admit that I personally measure success in terms of the contributions an individual makes to her or his fellow human beings."

"Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else."

"One of the oldest human needs is having someone to wonder where you are when you don't come home at night."

"I have spent most of my life studying the lives of other peoples — faraway peoples — so that Americans might better understand themselves."

"A small group of thoughtful people could change the world. Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has."

Monday, March 1, 2010

The Collectors

"I didn't play at collecting. No cigar anywhere was safe from me."

~ Edward G. Robinson

Last month the U.K. newspaper the Daily Mail published a fascinating story about the late Malcolm Guest, a British Rail employee who collected classic railway posters that would otherwise have been discarded for more than 40 years. Here are two examples.

It was only recently, when Mr. Guest died, that his family discovered the collection's value — an estimated £1 million — and poster aficionados learned of its existence.

Mr. Guest seems to have been a collector with a single, focused passion and a discriminating eye. But others are not so discriminating. My mother, whose compulsion was throwing things away, made an object lesson of the sad tale of Homer and Langley Collyer, the famous hoarders whose towering, boobytrapped heaps of newspapers, books, gardening tools, furniture and umbrellas (and more) led to their tragic undoing. Today, of course, cable television harbors a popular show about hoarders.

And then there are those who collect humans, like the protagonist played so chillingly by Terence Stamp in William Wyler's 1965 film The Collector. Based on the John Fowles novel of the same name, The Collector introduced us to Freddie Clegg, a lonely butterfly hunter who decides, instead, to hunt and hoard Samantha Eggar. The annals of true crime include all too many entries about real-life Freddie Cleggs.

And then there are those who collect humans, like the protagonist played so chillingly by Terence Stamp in William Wyler's 1965 film The Collector. Based on the John Fowles novel of the same name, The Collector introduced us to Freddie Clegg, a lonely butterfly hunter who decides, instead, to hunt and hoard Samantha Eggar. The annals of true crime include all too many entries about real-life Freddie Cleggs.

Freud famously blamed hoarding on poor potty training. In contrast, Mark B. McKinley, Ed.D., provides pleasantly easygoing theories about the psychology behind both collecting and hoarding on the Web site of National Psychologist magazine. He offers reasons from investment to fun to social contact to preservation of the past as drivers for true collectors. But even McKinley admits hoarders are a sadly different story.

Museums are, of course, the cathedrals of collecting. Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk's latest work, The Museum of Innocence (which I have not yet read, but absolutely must), is about a collector. In an interview about the novel on the Web site the Big Think, he said, "Museums put collectors on pedestals...But if there are no museums, then your habit of collecting, and also your collections, exhibits only your personal wounds....My character...likes the empty, melancholic old museums where no one goes...There you feel the venture of a prince, a rich guy, a sad guy, a poor collector who thought that he would transcend history by his collection, by his objects. But then it's how successful — no one comes."

Museums are, of course, the cathedrals of collecting. Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk's latest work, The Museum of Innocence (which I have not yet read, but absolutely must), is about a collector. In an interview about the novel on the Web site the Big Think, he said, "Museums put collectors on pedestals...But if there are no museums, then your habit of collecting, and also your collections, exhibits only your personal wounds....My character...likes the empty, melancholic old museums where no one goes...There you feel the venture of a prince, a rich guy, a sad guy, a poor collector who thought that he would transcend history by his collection, by his objects. But then it's how successful — no one comes."

As a side project, Pamuk has created his own museum and filled it with 83 objects. Judging by the brief sampling shown in this slide show on the Web site of the New York Times, it contain things that are not strange in themselves, but seem quite strange in this context. Pamuk said this about the collection to the Times: "I want my museum to be modestly filled with the ordinary things that make up the city, that make up any city. I want my museum to be a museum of the city, to include everything from street maps to locks to door handles to public telephones and the sound of foghorns."

Not everyone is a fan of museums. Consider D.H. Lawrence, who lived in the days when British museums were sacking and plundering the antiquities of the world, carrying them home as trophies. "Museums, museums, museums," he wrote, "object-lessons rigged out to illustrate the unsound theories of archaeologists, crazy attempts to co-ordinate and get into a fixed order that which has no fixed order and will not be co-ordinated! It is sickening!"

While I can understand Lawrence's ire, in the end I side with Margaret Mead, who said, “A city must have a soul, a university, a great art or music school, a cathedral or a great mosque or temple, a great laboratory or scientific center, as well as the libraries and museums and galleries that bring past and present together.”

Thinking about collecting and hoarding made me wonder about greed. Isn't the insatiable quest for more and more money a form of hoarding? We see it as hoarding when the ultra-rich binge on acquistions. Think of Charles Foster Kane. Think of the basement of Xanadu.

Thinking about collecting and hoarding made me wonder about greed. Isn't the insatiable quest for more and more money a form of hoarding? We see it as hoarding when the ultra-rich binge on acquistions. Think of Charles Foster Kane. Think of the basement of Xanadu.

So why isn't it also hoarding when money-collectors keep their assets in liquid form and store them in offshore accounts instead of vast basements? Maybe we should start thinking of those imbeciles on Wall Street as deeply neurotic. Maybe what they need is an emergency intervention. Maybe we should deliver it to them.

"I'd go stupid collecting and counting my money."

~ Thelonious Monk

~ Edward G. Robinson

Last month the U.K. newspaper the Daily Mail published a fascinating story about the late Malcolm Guest, a British Rail employee who collected classic railway posters that would otherwise have been discarded for more than 40 years. Here are two examples.

It was only recently, when Mr. Guest died, that his family discovered the collection's value — an estimated £1 million — and poster aficionados learned of its existence.

Mr. Guest seems to have been a collector with a single, focused passion and a discriminating eye. But others are not so discriminating. My mother, whose compulsion was throwing things away, made an object lesson of the sad tale of Homer and Langley Collyer, the famous hoarders whose towering, boobytrapped heaps of newspapers, books, gardening tools, furniture and umbrellas (and more) led to their tragic undoing. Today, of course, cable television harbors a popular show about hoarders.

And then there are those who collect humans, like the protagonist played so chillingly by Terence Stamp in William Wyler's 1965 film The Collector. Based on the John Fowles novel of the same name, The Collector introduced us to Freddie Clegg, a lonely butterfly hunter who decides, instead, to hunt and hoard Samantha Eggar. The annals of true crime include all too many entries about real-life Freddie Cleggs.

And then there are those who collect humans, like the protagonist played so chillingly by Terence Stamp in William Wyler's 1965 film The Collector. Based on the John Fowles novel of the same name, The Collector introduced us to Freddie Clegg, a lonely butterfly hunter who decides, instead, to hunt and hoard Samantha Eggar. The annals of true crime include all too many entries about real-life Freddie Cleggs.Freud famously blamed hoarding on poor potty training. In contrast, Mark B. McKinley, Ed.D., provides pleasantly easygoing theories about the psychology behind both collecting and hoarding on the Web site of National Psychologist magazine. He offers reasons from investment to fun to social contact to preservation of the past as drivers for true collectors. But even McKinley admits hoarders are a sadly different story.

Museums are, of course, the cathedrals of collecting. Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk's latest work, The Museum of Innocence (which I have not yet read, but absolutely must), is about a collector. In an interview about the novel on the Web site the Big Think, he said, "Museums put collectors on pedestals...But if there are no museums, then your habit of collecting, and also your collections, exhibits only your personal wounds....My character...likes the empty, melancholic old museums where no one goes...There you feel the venture of a prince, a rich guy, a sad guy, a poor collector who thought that he would transcend history by his collection, by his objects. But then it's how successful — no one comes."

Museums are, of course, the cathedrals of collecting. Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk's latest work, The Museum of Innocence (which I have not yet read, but absolutely must), is about a collector. In an interview about the novel on the Web site the Big Think, he said, "Museums put collectors on pedestals...But if there are no museums, then your habit of collecting, and also your collections, exhibits only your personal wounds....My character...likes the empty, melancholic old museums where no one goes...There you feel the venture of a prince, a rich guy, a sad guy, a poor collector who thought that he would transcend history by his collection, by his objects. But then it's how successful — no one comes."As a side project, Pamuk has created his own museum and filled it with 83 objects. Judging by the brief sampling shown in this slide show on the Web site of the New York Times, it contain things that are not strange in themselves, but seem quite strange in this context. Pamuk said this about the collection to the Times: "I want my museum to be modestly filled with the ordinary things that make up the city, that make up any city. I want my museum to be a museum of the city, to include everything from street maps to locks to door handles to public telephones and the sound of foghorns."

Not everyone is a fan of museums. Consider D.H. Lawrence, who lived in the days when British museums were sacking and plundering the antiquities of the world, carrying them home as trophies. "Museums, museums, museums," he wrote, "object-lessons rigged out to illustrate the unsound theories of archaeologists, crazy attempts to co-ordinate and get into a fixed order that which has no fixed order and will not be co-ordinated! It is sickening!"

While I can understand Lawrence's ire, in the end I side with Margaret Mead, who said, “A city must have a soul, a university, a great art or music school, a cathedral or a great mosque or temple, a great laboratory or scientific center, as well as the libraries and museums and galleries that bring past and present together.”

Thinking about collecting and hoarding made me wonder about greed. Isn't the insatiable quest for more and more money a form of hoarding? We see it as hoarding when the ultra-rich binge on acquistions. Think of Charles Foster Kane. Think of the basement of Xanadu.

Thinking about collecting and hoarding made me wonder about greed. Isn't the insatiable quest for more and more money a form of hoarding? We see it as hoarding when the ultra-rich binge on acquistions. Think of Charles Foster Kane. Think of the basement of Xanadu.So why isn't it also hoarding when money-collectors keep their assets in liquid form and store them in offshore accounts instead of vast basements? Maybe we should start thinking of those imbeciles on Wall Street as deeply neurotic. Maybe what they need is an emergency intervention. Maybe we should deliver it to them.

"I'd go stupid collecting and counting my money."

~ Thelonious Monk

Full disclosure: I am not a collector myself, but I do have far too many books and, at the same time, never enough.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)